Sciences of protection?

Professor John Law (Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University): how does control overcome complexity? The case study for this is the FMD outbreak centred on Pirbright.

The response to the current FMD uses surveillance and biosecurity to reduce the complexity of interactions between animals and other actors in the agricultural system, and to reduce the speed of these interactions. But why are those interactions so fast and complex? Firstly the world is geographically and economically stratified into zones: disease free vs diseased. Secondly the links between animals, famrs, people, machinery and trading places are many. Some of these are proximate and some are long distance.

Some comments on this:

1. attempts to order the agricultural system in 2001 were disordering: slaughter is disturbing; animal welfare is diminished, tourism is damaged, and the health and well-being of farming communities are affected.

2. The thesis of faster and more complex world is questionable in some ways. There are specific differences in organisation that affect complexity. This can be seen by looking at the role of the Common Agricultural Policy, BSE, more scattered landholdings, movements of animals.

We may be seeing a complexity escalation. Can control systems increase their capacity to match the increase in complexity? The State says yes. But also the control system can further increase complexity. Perrow’s theory is useful here. A tightly coupled system is exposed to accidents. Agriculture is structurally vulnerable because of tightly coupling. No tinkering can address these. We need to get into the basic politics and policy.

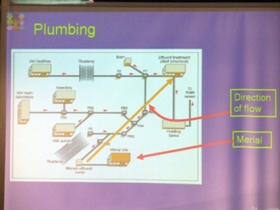

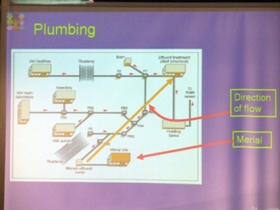

So to return to the Pirbright situation. Institute for Animal Health is a reference laboratory. It uses small amounts of FMD virus. Merial manufactures thousands of litres of FMD vaccine. The Health and Safety Executive report has investigated how the virus got out of Pirbright. The plumbing, and Dyno-Rod seems to be vital. An interesting diagram of plumbing was shown. Waste flows from Meriel to the waste treatment plant. The drains were in poor condition.

‘Containment was not achieved.’ Contractors were at work here too. Lorries were taking soil offsite. Overflows from manholes were picked up by lorry tyres, and then distributed along a route that passes by farms that later showed infection. But add to this the multiple logics at work here: divergent interests, different properties of the virus used to make vaccines, floods, contractors transporting soil, patchy maintenance of different era drains. An archaeology of drains shows that only parts of Pirbright were controlled. This is not glamorous.

So Pirbright is part of an agricultural safety system but adds complexity, disorder, and insecurity. It works through surveillance and control, but adds complexity, multiple logics and times. Ideology that responds to this: risk analyses, view failures as technical, the new will replace the old.

How to respond to this situation? Tighten control or accept impurity? The latter is better – find ways to accept complex, layered.

Respondents

Dr. Celia Roberts (Department of Sociology)

Thinking about protection in terms of the mundane and intimate – condoms, sanitary pads offering personal protection of the self – against pain and embarassment.

Wishes to suggest that even simple technologies can and do go wrong. They do not fail because they are complex but because they enrol people and bodies in real emotive, embodied social situations. They will work in some of these contexts and fail in others.

Much of John’s analysis of security and safety in agriculture may have resonance when thinking about human reproduction, for example, in the case study of Pre-Implantation Diagnosis (PGD) which is about enacting control to avoid children with a serious genetic condition coming into being. This is popularly referred to as the Designer Baby phenomenon.

Couples engage in PGD in order to avoid the potential and sometimes past feelings of suffering. Yet PGD does sometimes fail in the mundane ‘normal’ sense. Most people fail to ‘get what they want’ i.e. a healthy baby – the success rate is 20%. This is a failure in terms of people being without a baby and so may be seen as banal and non-dramatic, hopes dashed. The experience of PGD technology then may result in more suffering. Would more reproduction help? Or better social support or cultural innovations? Perhaps a social decoupling so that we can open up cultural ideas about human reproduction to have less biomedical ownership over the process and definition of experience. We need to think better about what the costs might be of investing our hopes in such technoscientific ways of managing security and protection.

Claire Waterton and Dr. Rebecca Ellis (Department of Sociology)

We have selected four issues from John’s paper which allow us to reflect upon our own interest in DNA barcoding which until now we had not framed in terms of security. We are more focussed upon experimental features of a design for a system. Like John we are interested in cases where insecurities pop up in surprising places.

Our case of DNA barcoding supports the claim that monolithic standards are too generalising and do not allow for adequate containment and control in modernist terms. We are interested in the current scientific and global project to ‘bank’ DNA samples of a whole range of species (there are at least 100 million on Earth) as an attempt (framed as such) to counter threats to biodiversity. Another interest is in the identification of virus carrying species and the prevention of bird strikes in airplanes!

For us this project speaks to a fear and inability for ‘us’ to completely capture knowledge of ‘nature’. Integral to the barcoder’s toolkit are various methods of purifying nature. Systems of biosecurity assume a certain notion of a future better life. What needs to be different for human and global survival? We draw upon Rabinow’s idea of purgatorial tropes to think through the present unease over the knowability of the future and fears over ordering technological systems and ‘nature’.

Barcoding uses a region of DNA called Cytochome Oxidase 1 (CO1), which is readibly usable, cheap and processable for identification and comparison of species. This has been adopted as the standard piece of DNA for the barcoding community to use. This is then referred against the barcode library of known, collated species. The ultimate dream is that one will be able to do this in the field with a handheld barcoder, thus improving radically the speed of coding and categorisation.

With the development of the system the barcoding HQ at Guelph (Canada) has had to open up to biodiversity. CO1 does not work for plants – so the current issue is whether a standard can be agreed for plant coding. A heated debate!

Whereas John ends his paper asking for the acceptance of vulnerability, we find a science generating a lot of material that has scope for contamination (also of the idea of uniformity).

Link to Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD)

Dr. Greg Myers (Department of Linguistics and English Language)

I begin with an image of the big STOP sign from the bird flu outbreak at the Bernard Manning Turkey farm.

Applied Linguistics as the study of real world problems where language plays a part. For example the case of HN51 entering our common language. My own area is analysing focus group transcripts in great detail, for example, discussions about security issues.

One way to see the function of STS is a counter to the view that science is seen as the solution to all our problems. Many of John’s examples of scientific ideologies involve everyday different ways of talking and interaction.

Focussing on the notion of proximity – space and place are crucial to security. But science presents itself as implicitly placeless (The god’s eye view). Proximity adds touch, is the result of everyday practices and speaks to identity and interaction. Security makes you rethink proximity. This will be developed further in the next workshop in the series.

Photograph from sldownard’s flickr account

More warning signs can be found here>

Filed under: workshop 1 | Tagged: animals, control, DNA, failure, language, life, PGD, space | Leave a comment »